Surat Al-Qamar (The Moon): 54:17

“And We have made the Qur’an easy to remember; so are there any that will study it?” (17)

وَلَقَدۡ يَسَّرۡنَا ٱلۡقُرۡءَانَ لِلذِّكۡرِ فَهَلۡ مِن مُّدَّكِرٍ۬ (١٧)

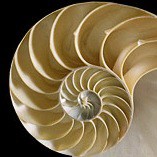

Note on 114 chambers: this stands for the 114 Suras of the Qur’an, which we shall see, during the course of this study, are arranged in the Qur’an in a very meaningful way. One can think of them, roughly, as chambers such as one sees in the chambered nautilus shell. This graphic comparison can be used as an aid to memorization as well as a gateway to comprehension and appreciation of the meaning and magnificence of this revelation, this message.

For Ramadan, I’ve decided to write an entry every day from my analysis of what I call Qur’anic architecture, that is, the structure and “design,” as well as what one could call “style,” of the Qur’an. As a revelation from Allah in Arabic to all humankind, the approach to this subject shall be one of reverence, but also intense interest in the deeper meaning of its content. Because for a book of this nature, style and content are necessarily closely related, this study is important, especially as I haven’t seen it done before.

The study will begin with some overall, general observations about which there is no issue or controversy, such as the general (and not strictly regular) decrease in length of the Suras from beginning to end, and the repetition of certain words and phrases. We will examine the significance of these and other structural elements carefully, bearing in mind that in this book, all elements are significant, especially the most prominent structural features. And where this will take us can only be, as we shall see, breathtaking.

The Quran frequently refers to issues relating to Truth and lies; distinguishing between them is critical, in many ways the defining point of guidance. In fact, faith itself is predicated on that distinction, the purpose of the Quran and other divine revelations being to guide us to the truth and, as a part of that guidance, to help us recognize and avoid falsehood.

The Quran frequently refers to issues relating to Truth and lies; distinguishing between them is critical, in many ways the defining point of guidance. In fact, faith itself is predicated on that distinction, the purpose of the Quran and other divine revelations being to guide us to the truth and, as a part of that guidance, to help us recognize and avoid falsehood.