Harmony between opposites: how difficult is that? VERY, apparently. Yet how rewarding: in a society, it brings mutual cooperation and the resurgence of the common good — and how elusive is that in the modern world! In individuals, balancing opposites, exemplified in the concept of Yang and Yin, opens up the possibility of real and enduring love and success in the higher sense. Surat Al-Shams addresses the human capacity for these ultimate opposites: immense harm and immense good, each with — who hasn’t seen it? — immense consequences. Of course, now, on top of species going extinct, extreme climate changes, and predatory economics, we have a horrific genocide that nobody seems willing or able to stop, live-streamed into our homes. When I first wrote this post (but did not publish it), long before the siege on Gaza, this part was different, but the subject matter of good and evil is very much the same.

This surah compares the most important natural phenomenon of light — the sun/moon and day/night — to the nafs or “conscience/self” and its capacity for evil/criminality or righteousness and goodwill. Sometimes the suffering caused by evil or harmful deeds brings forth from a complacent humanity their heroic and righteous side. We can see that happening also as the genocide metastasizes. In this sura, this theme is illustrated by the story of Thamud and the she-camel in a both visceral and symbolic way. An essential short but deep dive into what it means to be human.

The Sunlight of Conscience vs the Darkness of Denial

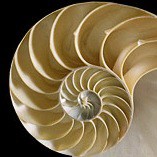

In the first six verses/ayat of this surah, Allah swears by pairs of related natural phenomena: the sun/moon, day/night, and sky/heaven/ earth. (In the Quran “sky” and “heaven” are the same word – “paradise” aljanna is an entirely different word, a place of being rewarded to those who passed the test of this worldly life.) The way they are described is very significant, each showing a kind of alternation between opposites, like yang and yin, shown in the illustration by the alternating yellow for yang and blue for yin ayat. The aya in green represents the central theme, like a balancing fulcrum, which describes the two basic paths of good and evil we have to choose from. In creation (“nature” in modern sterilized usage), we are given an example of the dynamic harmony of this. In the Quran, we are given guidance on the symbolic nature of creation, and how to live our lives to reach a state of fulfillment and purpose, where Allah’s acceptance is the ultimate success – beyond our wildest dreams.

- Light/Sun (Yang): “The sun and its morning brightness” presents the sun in its most beautiful face, its first freshness and relief from night, past dawn but not yet so hot as noon. The light of the sun is unique in how its heat and light can be beautiful and golden, beneficial to us, enlightening even to the spirit. This is then likened to the self/soul/conscience (all actually one entity) — our person, our very being, created radiant by Allah’s grace, recognizable in those we love, or others whose actions are essentially good. This describes the best of or ideal concept of Yang. It includes knowledge, power, creative energy, radiance, and inspiration.

- Moonlight in the Dark (Yin): “The moon when reflecting it” — the word talaha is usually translated “following” which is the literal meaning of the Arabic, but in this application implies “following” the sun’s light, rather than its “trajectory/path”, although it also implies the moon as being in a subordinate position vis-à-vis the sun. This understanding — of the moon reflecting the sun’s light — was understood in the past in a non-scientific but meaningful way — the modern sense was not known until more recently. This represents how the self/soul can “shine” even during the times of darkness, “reflecting” its inherent or “inner” light, that within the heart. It also represents the best of the ideal concept of Yin which is receptivity, the qualities of mercy, patience, enduring love and nurturing, responsiveness, and submission to the “best of Yang” which is perfectly expressed by Allah the Exalted alone, Who also expresses the highest form of both Yang and Yin in perfect yet dynamic balance.

- Day (Yang): Time is then introduced, first with “the day when displaying it” — jalaha being a word used for “showing off” the best of something beautiful — hence the day is a timeframe in which the sunlight can be fully displayed. This tells us that the self/conscience (as inner “light”) will experience times when its radiance is apparent. We are expected in such times to strengthen and develop it. This is to show us that time also has yang and yin aspects; these represent our circumstances, to which we are subjected just as the sun and moon are subjected to circumstances and time. Time is another layer or aspect of creation, this world, and our lives.

- Night (Yin): In contrast, “night when concealing it” or “enshrouding it” reminds us of Surat Al-Layl 92 where the same root word yaghshaa (“concealing/enshrouding”) is used to describe night, and here, as there, it means obscuring the self/conscience, a time of weakness for the soul’s light, when we will need to use the reflected and inconstant (waxing and waning) light of the moon, something akin to “the still small voice within.” At such times, we are tested, and need to listen harder or notice more deeply our situation, so as not to be overtaken by worldly influences. The sun, like the soul, is subject to the influence of time which alternately displays and conceals it. And the moon’s light appears more clearly when the sun’s light is concealed, thus its influence too is subject to time. The soul/conscience too is subjected to time, thus we are informed of our limitations. Yet in all this, there is a dynamic harmony: the moon is in the receptive “yin” position to the sun’s light-radiance, but in the context of night, it reflects the sun’s yang characteristic and so it is also the “yang” (illumination) to night’s “yin” or darkness. And the Quran is replete with descriptions of the benefits of night and day’s alternation — the night allows us to rest and refresh our bodies and minds, and also to contemplate, to feed the soul after the necessary work done during the day.

These first four ayat

also contain four (Arabic) words each, and are thus tied together with the “heart” (its symbolism in the 4 chambers) wherein the soul/self/conscience resides, which is then elucidated in subsequent ayat. The harmony with which the celestial objects, sun and moon, are arranged in time, day and night, can remind us of music, of symphony, insofar as music in its higher forms can exemplify harmony in time, expressing time in a potentially beautiful or “soulful” way.

The subsequent three ayat 5-8 have 5 words each, symbolizing “hand” (as in 5 fingers), in this case the “hand” of God in these verses that refer to Allah not as “Who” but “what” — in the sense of “what power” or, to use William Blake’s expression, “what immortal Hand or Eye” and one can even complete it with an implied “dare frame such fearful symmetry” inspiring awe. This is of course referring to the creation of the sky/heaven (aya 5) and the earth (aya 6) and, lastly, the creation of the human being and his “self” (aya 7). All these are Allah’s creations; it is implied that humans — both bodies and souls/selves — are created from elements of both realms, the heaven and the earth. These realms are also symbolic: the heavens represent the “celestial” realm, not merely the sky as a physical entity, but the eternal dimension. Similarly the earth represents “this world” in the sense of worldly pursuits as distinct from pursuits done for the “Face of Allah” and the Hereafter or, more pointedly, a timeless realm we cannot perceive with our “senses five.” Thus we have:

- “The sky and what (kind of power) built it,” or one could say “the heaven and what ‘immortal Hand or Eye’ built it” showing us the “Yang” Creative power of the Almighty; it is at a remove from us, although we’ve always sought to penetrate it, at first with our minds including our imagination, and later with our own inventions and their implementation (space travel). Allah the Exalted swears by a creation which, the more we fathom it, the more detailed our amazement becomes — for those capable of amazement and awe, that is.

- “The earth and what (unimaginable power) spread it” — the word for “spread” (a word only found in this form in the Quran in this surah) one can imagine refers to the infinite variety of the earth’s surface, with mountains, valleys, plains, and innumerable features in between. The earth’s crust is the magnificent ground upon which life thrives, including aquatic life — water being the most vital part of its surface. It is associated with “Yin” or receptivity, yielding. But to be in harmony with it, we must have a reverent attitude, a sense of balance.

Again, our attention is drawn to two “opposites” which are in a kind of dynamic harmony, whose very complexity is itself a source of inspiration and contemplating what’s beyond our understanding.

So, next Allah swears by the soul or self in ayat 7-10. This emphasizes the significance of the self as four whole ayat are devoted to it. And 4, as we’ve said, is a number that symbolically represents the heart. The section in green is in fact the center fulcrum of this sura. Now we are asked what balanced the self, further elucidated by saying this balance is “what makes it a violator or a guardian,” which is to say a sinful – violator of Allah’s commands and people’s rights enshrined in those commands – or a righteous person – guardian of Allah’s laws and our commitments/ covenants with Him, as well as an attitude of compassion, generosity, and respect for the basic dignity/sacredness of life.

The translation above takes into consideration the linguistic elucidations of Nouman Ali Khan (whose explanation of this surah is linked at the end of this post) in the word “balanced” as key to aya 7, and “works to purify” instead of merely “purifies” in aya 9, the latter to clarify that we cannot fully purify ourselves — only Allah can — but it is our effort that is rewarded.

This is an important distinction because self-righteousness is an impure attitude, the one who thinks himself pure (having achieved purity) and setting himself up as an idol. We must always strive for humility, knowing it is a struggle and a process, not an “achievement” in the sense of attainment after which one “rests on one’s laurels.” This too is a balance, avoiding the extreme of self-humiliation, and instead maintaining a reverent attitude. The translation “violator or guardian” is described below, noting that both require some effort on our part.

Aya 7: “By the conscience/self and what balanced it” — these words cannot be translated really by a single word. The nafs encompasses all these words: soul, self, conscience. In modern English, these terms are used separately, as a person is thought of more as a physical than a spiritual being, as if the person’s “essence” is nonexistent except as “properties” of his physiology or body. “Consciousness” — the awareness of things that comes from the same thing as soul, self, conscience, essence — is a “problem” for scientists. The “soul” is assigned to religion; “enlightened” people “know” it not to exist, unless “enlightened” in the “mystical” sense, which has been harnessed by popular culture as “meditation.” A useful practice, but divorced somehow from “conscience.” One can meditate and then go on oppressing others, or maybe think twice about it, or maybe not.

“What balanced it” is really “what immortal Hand or Eye balanced it” — this word ma means “what,” not “Who” although most translations express it as “He” or “Who” or “the One,” as it feels wrong to address Allah who clearly is referred to here as “what” — but this word is often used this very way in the Quran for a reason. Which is, to make us think: what power and might, what attributes would it take to create this, to perfect this, to balance this? The word “balance” I use here because it refers to balancing two opposites, just as in the previous oaths the celestial bodies and time are described as a balance of opposites. It has also been translated “proportioned” or “fashioned” or other expressions of “formed,” but the word suwaha emphasizes the balance of two potentialities in the human soul.

Aya 8 “Then inspired it with what makes it a violator or guardian.” This is the central aya/verse or “fulcrum” of this surah, showing us our choice between the soul’s capacity for fujur or doing extreme harm, to intentionally violate ethical norms, pitted against its capacity for taqwa, which term embodies reverence, God-consciousness, and the intuitive drive to guard against that fujur, which represents evil, the same word used to describe Satan.

This translation is based on insights from Nouman Ali Khan (the word taqwa contains the idea of protection) and this creation of Adam narrative in Surat Al-Kaf (18), the original translation (from the Study Quran) being “what inspired it with what makes it iniquitous or reverent,” which meaning is also implied here and is quite eloquent. However, adding the meaning of “protection” as well as “reverence” and “mindfulness” means we must choose to be guardians against evil via taqwa, true God-fearing which activates our conscience. To “violate” has in English the more emphatic sense of fujur in Arabic, a word for the most extreme willingness to violate all that we collectively know as Good, True, and ethical.

Often it’s translated “rebellious” and was used to describe Satan. But in English, “rebellion” can have a positive connotation; one can rebel against oppression in behalf of justice. But fujur is not so easily appropriated for that kind of usage. It’s the mindset of a persistent violator of others. It’s always in the Quran used to refer to oppression, never a fight for justice. We intuitively sense right from wrong. But our ability to “rationalize” means we can counter-argue against our own intuition, and when we finally “succeed” to obscure that Divine gift (as night covers day), then we are truly lost and this brings out the worst in us unimpeded by that now-smothered light, thus we become violators. That fujur seeks to create a world where even the “moon” is obliterated.

In this central aya, Allah the Exalted warns us that the capacity for good and evil both lie within ourselves, and it is our job, our very purpose in life, to develop our best selves. It is a struggle; suffering actually helps make it easier; and we are fully responsible not for perfection — that’s Allah’s purview — but for putting effort/work into choosing to be guardians of what is Good. And this is something we all intuitively sense. Both losing that sense and developing it take time, a process, but direction is an important element here — where do we direct ourselves? We can reset our compass by remembering Allah.

Notice the translation (mine) “works to purify it,” because only Allah can fully purify us. The word zakaha does mean simply “purify it,” but the effort is implied in the Arabic whereas in English the end result has prominence over the effort. “Are you purified?” Is an end-result question, but in Arabic the verb refers to the process. We are asked to work at it; the outcome is with Allah. And this is generally true of all our efforts. And the word translated “prosper” is more accurately “succeeds,” although to prosper is an ongoing success and in that sense appropriate. This success is not a one-off, but a continuous state, in this life contingent upon continuous effort. And what purifies us? What work is this? Always the answer is clear: dhikr Allah (mentioning and remembering Allah) and charitable giving, helping those in need in particular.

The Example of Thamud as Violators

Who are the Thamud?

This site describes them briefly like this: “Among the most prominent civilizations were the Thamud civilization, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to around 300 CE.” The date 300 CE puts their demise around 300 years prior to the birth of Prophet Mohammad and thereafter the sending of the Quran by the Lord of the worlds to the prophet’s heart. This date, however, is by no means hard and fast. At any rate, a civilization of such prominence in the Arab world would have been well-known, and their demise legendary. I first noticed their name on a map of the region in a lecture on pre-Islamic Arabia and its language, which referred to the era after the death of prophet Jesus. Certain dwellings carved into mountains in what is now Saudi Arabia are claimed to have been built by the Thamud.

What is important here, however, is not the history of the Thamud as studied in modern times, concerned with where they lived, what exact time period, did they have a written language and if so what did it look like, did they have a relationship with the Babylonians (always a favorite question) etc. What the Quran is concerned with here is that they were an impressive group of people in terms of strength and the size/strength of their dwellings which were carved out of solid mountains’ rock, but became arrogant, especially their leaders and those with political power, who rejected the message of the prophet Allah sent them, Salih.

They were also oppressing their own as well as other people, lording it over them, so Allah sent them, as a test, a she-camel who drank large quantities of water on a specific day during which they were prohibited to drink except a little. They came to resent this she-camel, thus Salih told them that Allah forbade them to harm her. Sometime thereafter they hamstrung and killed her, a way of showing their disdain and opposition to prophet Salih, and even more, their rejection of Allah/God as One, insisting to worship only the gods of their forefathers. And in the case of the she-camel, getting rid of her with cruelty, while she was described as “God’s she-camel.” Thus Allah destroyed them for their cruelty to the she-camel and rejection of Allah and his prophet, after giving them many chances to change their minds and amend their behavior.

So the message here is the same consistent message given throughout the Quran: Allah/God invites us to the path of conscience and justice between one another and the natural world/creatures and ecosystems around us. Thus we worship only one God/Allah Who loves justice and righteousness and compassion, not human leaders or celebrities who only care about their personal interests in this brief world of time and reject the idea of a Hereafter, reject God and the morality and reverence He enjoins on us to become the best most worthy people we can be. The problem with multiple gods is we invent them to our liking – whether celebrities, desires, or statues as the ancients worshiped – to serve our own self-interests, and thus have no higher guidance from the Omniscient All-Merciful. Allah rewards and punishes the strong and the weak, the rich and the poor, the person of high or low stature in society, all on the same basis of piety and moral, righteous behavior. So may we all be guided to His truth, to the joy of His Presence and giving, and thereby to the fulfilling of our heart’s desires in Al-Akhira, the Finality or Hereafter.

Part One and Two of Nouman Ali Khan’s explanation of Surat Al-Shams 91.